For those unfamiliar with the concept of NLP1, our old friend Wikipedia explains that it's a system for exploiting the existence of "...a connection between the neurological processes ("neuro"), language ("linguistic") and behavioral patterns learned through experience ("programming") and that these can be changed to achieve specific goals ...".

A pragmatic exponent of some of NLP's more entertaining applications (and vocal critic of much of the exploitative psycho-quackery built around it) is the charismatic brain-squeezer Derren Brown. He offers this rather simple explanation;

"by paying particular attention to the language we use, we can have a powerful effect on the unconscious neurological processes of the listener" - Tricks of the Mind, p176Of course all political parties use carefully chosen language to try and programme the electorate to their way of thinking; we live in an age of endlessly repeated soundbites, of pithy phrases designed to penetrate the consciousness of the short attention-spanned. But what sets the SNP (the SNLP?) apart is the sheer audacity with which they're willing to relentlessly repeat not just partial truths but demonstrable falsehoods.

The mainstream media sometimes (although all too rarely) highlight the dissembling duplicity of the SNP's public pronouncements, but the SNP have immunised themselves against this by spending years patiently undermining all media sources except those they favour (which funnily enough tend to be the ones they have created or effectively control). It could be argued that the SNP's most impressive achievement has been to enable their supporters to give themselves permission to ignore all dissenting voices.

By their very nature, you'll be familiar with the sorts of phrases that I'm referring to.

Firstly there are those partial truths that focus on GDP or tax revenue but simply ignore spending (like judging the quality of a business on its revenues not its profits). These statements blithely ignore what it costs to run our country with the levels of public service we've become used to

- "[Scotland has] paid more tax per head of population every year for the past 34 years."

- "Scotland's GDP per head is £2,300 higher than UK as whole"

- "Scotland is the 14th richest country in the world"

These carefully chosen and endlessly repeated boasts were of course all dependent on oil revenues, so they're no longer valid. Take a meander through the remoter natwaters of social media though, and you'll see that plenty still believe and repeat these half-truths.

Secondly there are those statements that, by any reasonable analysis, are simply false. Here are just a few

Secondly there are those statements that, by any reasonable analysis, are simply false. Here are just a few

- "We send more to Westminster than we get back"

- "Independence would have made Scotland £8.3bn better off over the last 5 years"

- "Oil is just a bonus"

- "We will plan Scotland's public finances and borrowing requirement on the basis of a cautious forecast for oil and gas revenue"

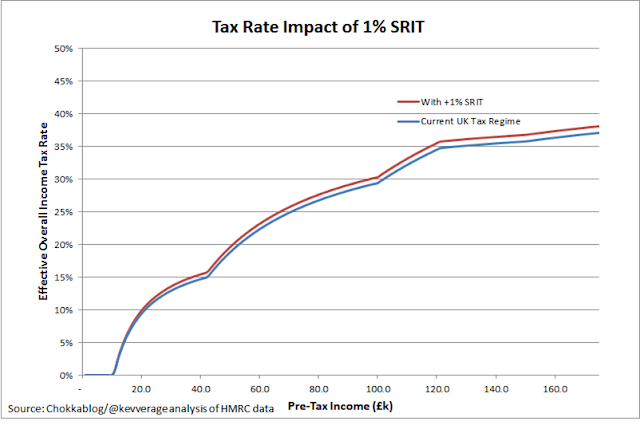

- "[SRIT would have] about double the effect on the taxable income of individuals at the lower income thresholds rather than people at higher income thresholds"

Finally there's a category which is perhaps the most NLP-y of all: statements that can't be factually refuted and that imply (or explicitly claim) inevitability.

Perhaps the most notable example of this during the indyref was "Are you Yes yet? The clear implication being that you inevitably will be, it's simply a matter of time. To be fair this is simply an example of good campaign language. I offer no criticism in this instance, just polite applause.

But for me the most insidious example is "A Second Scottish Independence Referendum is Inevitable". This statement has the capacity to become a self-fulfilling prophesy if we allow it to become received wisdom.

As a rule, people don't vote to make themselves poorer. The last indyref took place in the context of a period where - if you ignored up-to-date data, shut one eye and blurred the other when looking at historical figures and were willing to believe hopelessly optimistic oil forecasts - you could just about persuade yourself independence wouldn't make us worse off. Those of us who looked closely quickly drew a different conclusion.

As as aside; I don't believe the fact that it would make us immediately worse of is in and of itself a reason not to vote Yes; but I do believe those campaigning for a Yes vote had a moral duty to be honest about the economic implications. This blog's existence is a direct result of the fact that they weren't, of my frustration with the transparent dishonesty of the Yes campaign's claims.

Now - following the collapse in oil revenues - it's clear Scotland would be £8bn2 a year worse off as an independent country if all else stayed the same (which of course wouldn't be the case3). The best spin-machine in the world couldn't hide that fact under the intense scrutiny another referendum campaign would bring. No amount of artificial grievance-mongering or empty "social justice" rhetoric would persuade us to vote to make every man, woman and child in Scotland immediately £1,500 a year worse off .

As as aside; I don't believe the fact that it would make us immediately worse of is in and of itself a reason not to vote Yes; but I do believe those campaigning for a Yes vote had a moral duty to be honest about the economic implications. This blog's existence is a direct result of the fact that they weren't, of my frustration with the transparent dishonesty of the Yes campaign's claims.

Now - following the collapse in oil revenues - it's clear Scotland would be £8bn2 a year worse off as an independent country if all else stayed the same (which of course wouldn't be the case3). The best spin-machine in the world couldn't hide that fact under the intense scrutiny another referendum campaign would bring. No amount of artificial grievance-mongering or empty "social justice" rhetoric would persuade us to vote to make every man, woman and child in Scotland immediately £1,500 a year worse off .

The SNP have been clear there won't be a second referendum unless they believe they can win it; they won't win it if a Yes vote would obviously make us all poorer. So what could change the fundamental economic situation, and are any of these things "inevitable"?

- Another windfall source of revenue could be found that generates £8bn+ a year in tax revenue and has the appearance of being sustainable. This could be oil & gas again (although the oil price simply returning to $100 won't be sufficient, as I explain here) or it could be we discover some other swiftly tax generating natural resource.

- Scotland's economy could miraculously boom such that our GDP (and therefore our tax revenue) growth outstrips that of the rest of the UK by 16% (the amount required to generate £8bn pa more income). The notoriously optimistic Independence White Paper itself argued that such levels of growth would take generations to deliver. There has been no credible case put forward for why further devolution (or indeed independence) should create superior growth for Scotland - the logic goes little further than "because Scottish people making decisions for Scotland"

- The drive for more powers for Scotland could lead to the Barnett formula being scrapped or drastically altered. The Barnett formula underpins the calculation of the block grant, the block grant provides us with funds for public spending that's currently £8bn pa. more than our proportionate share of (current) tax generation would allow. Take this away - stop us from benefiting from the "pooling and sharing" that protects our public spending - and we lose the single strongest argument against voting Yes: the £8bn a year Union dividend.

The third of these is of course made more likely by the SNP's persistent winding-up of the rest of the UK. If they persuade everybody that indyref II is inevitable it further helps their cause - why should the rest of the UK continue with pooling and sharing if it's inevitable that Scots will leave soon anyway?

So next time somebody tells you that a second independence referendum is inevitable, maybe ask them why - then judge for yourself if you think their opinion has been reached through reason or programming.

So next time somebody tells you that a second independence referendum is inevitable, maybe ask them why - then judge for yourself if you think their opinion has been reached through reason or programming.

*******

1. I'm using the term NLP as a convenient short-hand here, on the assumption that these basic principles are widely understood and easy to grasp. I think the wider NLP "industry" is well described by Derren Brown: "a huge industry of daft theories and hyperbole, evangelical mind-sets and endlessly self-perpetuating courses ..." - Tricks of the Mind p.177

2. The £8bn is a conservative estimate and comes not just from my own analysis but also the highly respected independent think-tanks IFS and NIESR - I summarised these most recently here

3. Those things that "wouldn't stay the same" carry more downside risk in the short-term (issues around currency, trade, capital flight and transition costs) and the (highly debatable) upside benefits would take generations to materialise.