"In war, moral power is to physical as three parts out of four"Debates about the United Kingdom's place within the European Union or Scotland's future within the United Kingdom are often framed as being about "head" vs. "heart".

Napoleon, 1808

The Brexit result is explained as happening because emotionally inspiring rhetoric about "taking back control" captured voters' imagination in a way that wearisome warnings of slower GDP growth simply couldn't. In part this was a function of the way the Remain and Leave campaigns were fought but, bar some rather unlikely scenarios involving another referendum, those arguments are now past.

But whereas our place in one 45 year-old union may be lost, the integrity of our existing 311 year-old union is still very much up for grabs. Many of us who feel a sense of dislocation and loss about Brexit continue to fear for the future of the United Kingdom itself. Whatever one's views on Brexit, those who care for the integrity of this older union should think long and hard about how we make our case.

This matters because when narratives take hold, they can be hard to dislodge. We run the risk that tactical decisions taken in the heat of the last battle become accepted as strategic wisdom for the next.

In the case of the ongoing Scottish Independence debate, an all too widely accepted narrative is that Scots' emotional desire for independence is dampened when faced with the stark reality of the economic pain that would be involved - that economic pragmatism trumps emotional ambition.

This framing of the debate is superficially persuasive but deeply flawed.

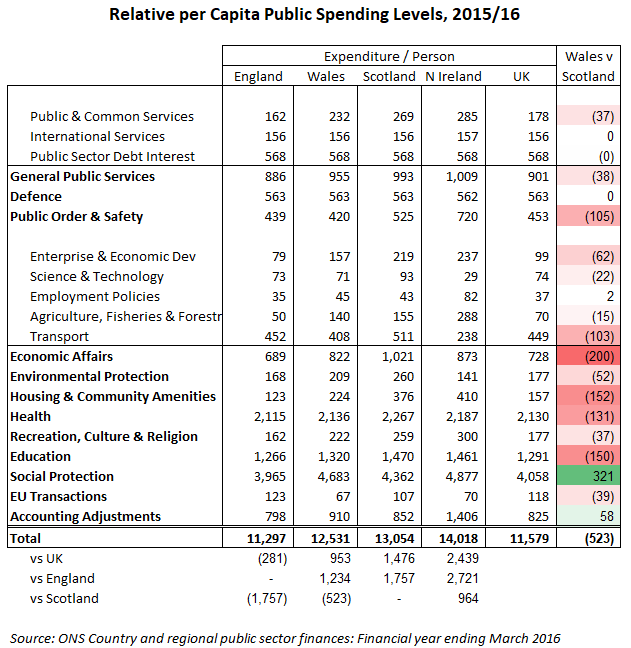

If we rely on a utilitarian economic argument to persuade people to remain in a union, how do we sell that union to those who lose out based on the same narrow economic logic? If our arguments are limited to only the selfish economic case, where do we turn to if - say as the result of another dramatic oil boom - the fiscal transfer arithmetic changes?

The truth is that not only is there a strong emotional case for union, but that "head" and "heart" are inextricably linked. The economic arguments only exist because they're underpinned by an emotional bond. At its core, the decision to pool and share resources is a moral one, based on a shared sense of responsibility for the social welfare of our fellow citizens. Put simply: the head doesn't keep functioning for long if the heart isn't there.

This artificial separation of "head" and "heart" - and with it the implicit ceding of the emotional ground to the Scottish Nationalists - is in large part a function of the way the 2014 Independence Referendum was fought.

The No campaign judged that the economic arguments against independence were compelling and would be persuasive to those voter who were either soft Yes, undecided or wavering No. Elections and referendums are won and lost among these all-important swing voters and Better Together took the tactical decision to focus on targeting them with the compelling economic arguments.

In the white-heat of a campaign period, that decision to focus on the practical at the expense of the emotional was probably tactically correct. Critics of the Better Together campaign - myself included - would do well to remember that they won the referendum. As time passes and we find ourselves in a post-Brexit, post-Trump world, the achievement of winning against a populist, emotionally driven, fact-denying and mainstream-media bashing Yes campaign looks increasingly impressive.

In contrast, the Yes campaign unsurprisingly judged that an honest presentation of the economic consequences of independence would be a vote loser. So they sought to obfuscate and misdirect when it came to financial matters and instead focused on the emotional case.

This was most clearly demonstrated in the 649 page Independence White Paper, in which the SNP couldn't find room for anything that could credibly be called an economic case. Instead they just forecast a ludicrously optimistic starting point where North Sea tax revenues would be £6.8 -£7.9 billion a year, provided no answer to the currency question and assumed and there would be no economic downsides of separation.

Those highlighting the recklessness of relying on such optimistic oil revenue forecasts were met with the logically nonsensical assertion that "oil is just a bonus" - a "bonus" on which the White Paper's spending promises were entirely reliant. Those asking what currency we'd use and what fiscal constraints would result were dismissed with meaningless soundbites like "it's Scotland's pound and we're keeping it". The Treasury's economic forecasts were scoffed at as being a "dodgy dossier". To question the lack of an economic case was to be accused of "talking Scotland down". Economic arguments that appealed to the head were sneeringly dismissed as "Project Fear".

The SNP lost the independence referendum in large part because these attempts to dismiss rational arguments failed. It's somewhat amusing to see them now enthusiastically promoting similar - but frankly far less compelling - rational arguments in their opposition to Brexit.

To achieve support even for the idea of another independence referendum, the SNP recognise that they'll need to fill the vacuum that still exists where their economic case should be. In September 2016 they created a "Growth Commission" and gave them the unenviable task of creating an economic case for dragging Scotland out of the UK single market.

In March 2017 the Commission's report was "due to be delivered to the first minister in the coming weeks" but, as we enter 2018 and near the second anniversary of the Commission's formation, still nothing has been published. The lengthy delay suggests that the Commission’s desire to be credible may be clashing with the Party’s desire for the case to be palatable. We wait with bated breath to see which wins.

But those of us who argued to keep the United Kingdom together during the independence referendum can't afford to be complacent. We have to face the difficult truth that the economic illiteracy of those campaigning for independence was nearly matched by the emotional inarticulacy of those of us campaigning for union.

The strength of the UK lies not just in what we share financially but in what we share emotionally: values, history, culture, belief in liberal democracy and a willingness to share responsibility. Perhaps it’s time we started talking less about the cold economic logic of fiscal transfers and more about the bonds of moral solidarity that bind us.

***

To think intelligently about how to frame the ongoing debate, we have to first step back and recognise that the way the battle lines are currently drawn is down to the circumstances of the time rather than anything fundamental about the nature of arguments for and against union.

If you're not convinced, try this thought experiment: how would the campaigns have been fought if the independence referendum had been held in the mid 1980s when oil revenues were booming and "Scotland's oil" made Scotland a very significant net contributor to the UK's finances? We can safely assume that the Yes campaign would have been fought far more on rational economic grounds ("it's our oil", "We send far more to Westminster than we get back") and the No campaign would have focused on softer arguments about moral solidarity and our history of shared endeavour.

We should also be clear that this is not about positive versus negative arguments.

The Yes campaign may have been more focused on the emotional, but it most certainly was not and is not a positive campaign. Ask any journalist, creative artist or businessperson who had the temerity to speak out and argue for the union during the independence referendum, scan social media to see the levels of abuse they (we) still receive to this day. Observe SNP politicians' transparent attempts to mislead about the Scottish Government's own export data and their desperate attempts to undermine the credibility of their own GERS reports (when the numbers don't suit them). At its most sinister, see how some in the "Yes movement" seek to other the English, caricaturing them as heartless racists, creating a cartoon-villain "them" for "us" to rail against. The Scottish Nationalists may appeal to some base emotions, but there's very little positive about it.

Similarly, there's nothing inherently negative about the economic arguments in favour of union. If you're yet to be convinced of that, bear with me.

If we're to create a case that combines Napolean's one part physical with the three parts moral, we need to get right back to basics and take a holistic view of what makes a union work - and that, my weary reader, is what we'll focus on in Part II.